Ainsworth, A Revised History

The story of the Ainsworth meteorite began in 1907, according to Edwin E. Howell’s description of the iron in the American Journal of Science, Vol. s4-25, Issue 146, February 1, 1908 (DOI).

Howell wrote that the meteorite “was found last winter by one of Mr. W. G. Townsend’s little boys, who called his father’s attention to it as it lay partly buried in the sand beside a small creek in Brown Co., Nebraska, about six miles N.W. of Ainsworth...”

And, since 1908, that’s how everyone thought this meteorite was found.

But…there’s a small problem with that story…

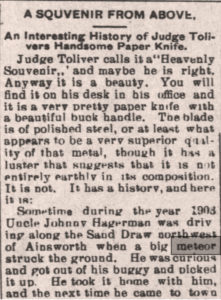

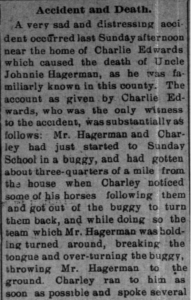

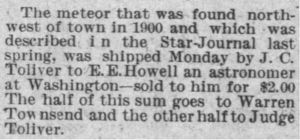

From the Ainsworth Star-Journal, January 18, 1907 — published a year before Howell’s article in the American Journal of Science, and apparently several months before Townsend’s son “found” the meteorite:

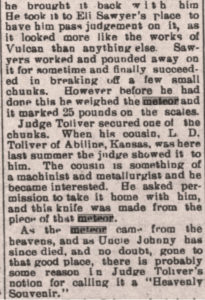

The above article states that the Ainsworth meteorite wasn’t found in 1907, as Howell reported: it was actually discovered several years prior, in 1903, by “Uncle Johnny Hagerman.” At the time, a local judge and Civil War veteran, James Calloway Toliver, took an interest in the object and he obtained a piece of the meteorite by, at the latest, sometime in 1906.

There are a few details here worth noting:

1) The iron weighed 25 pounds when it was found, and it probably weighed a bit less after Eli Sawyer removed a few “chunks.”

2) As of January 18, 1907, the meteorite, which belonged to “Uncle Johnny,” was missing.

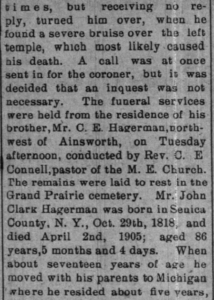

3) John C. Hagerman had passed away in a horse-drawn buggy accident in 1905, about two years before that article about the judge’s otherworldly paper knife was written:

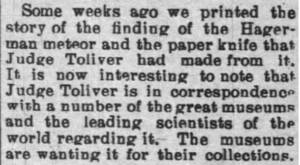

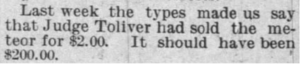

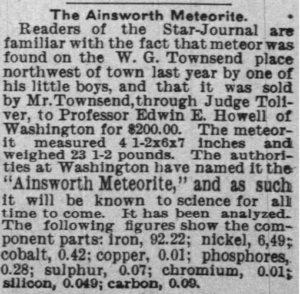

After publishing the January 1907 article about the paper knife, the Ainsworth Star-Journal published several updates about the meteorite, from May 1907 through February 1908:

The Star-Journal’s first article about the Ainsworth meteorite, published on January 18, 1907, stated that, after “Uncle Johnny Hagerman” died in 1905, the iron had mysteriously disappeared: “When he died, it could not be found, and it has not since been located, though dilligent search has been made all over the place fo it.” [sic] So, by January 1907, it had been missing for about two years.

Although the newspaper documented the rest of the meteorite’s history and journey in detail, the story of its rediscovery, sometime between January and May* April of 1907, strangely seems to have been omitted at the time. When the newspaper picked the story back up on May 10, 1907, the iron was already in the possession of Mr. William G. Townsend and Judge Toliver, with no explanation of how they’d acquired it. According to the paper, in May, “Judge Toliver [wa]s in correspondence with a number of the greatest museums and the leading scientists of the world regarding [selling] it“; by August 16, he had brokered the meteorite on behalf of Townsend to E. E. Howell, for $200. The paper reported that Toliver and Townsend split the proceeds.

*Thanks to a letter from Newton H. Winchell, a Minneapolis geologist, preserved in the papers of Herbert P. Shunway, we know that Judge Toliver had made contact with prospective buyers at least as early as April 1907, so it must have been “rediscovered” soon after the January 18 article was published.

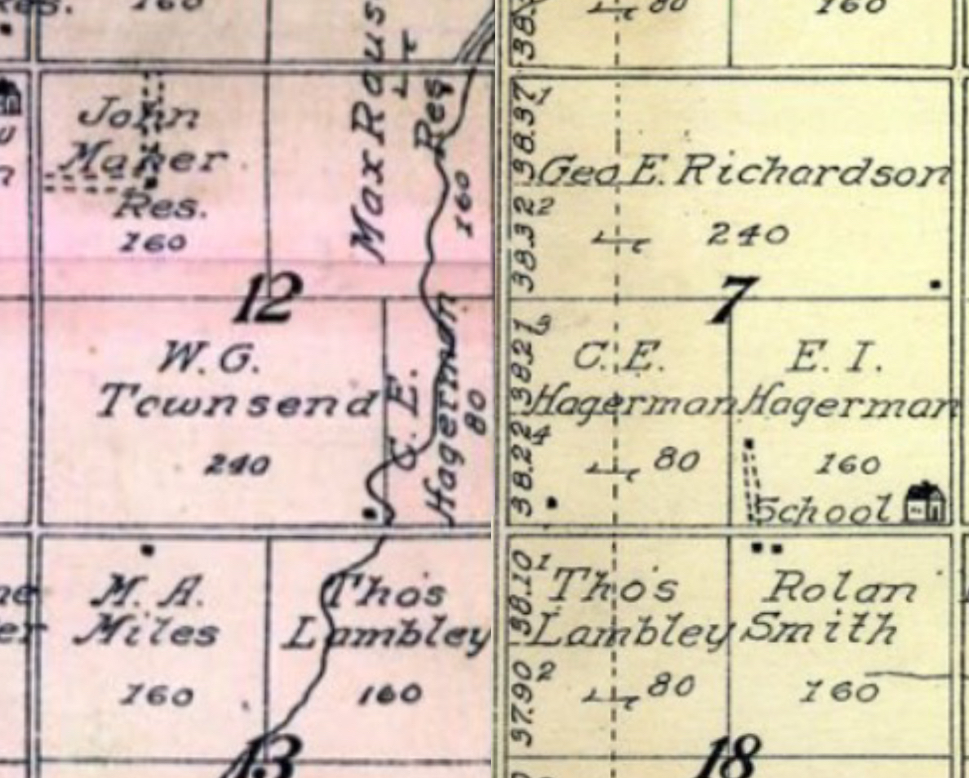

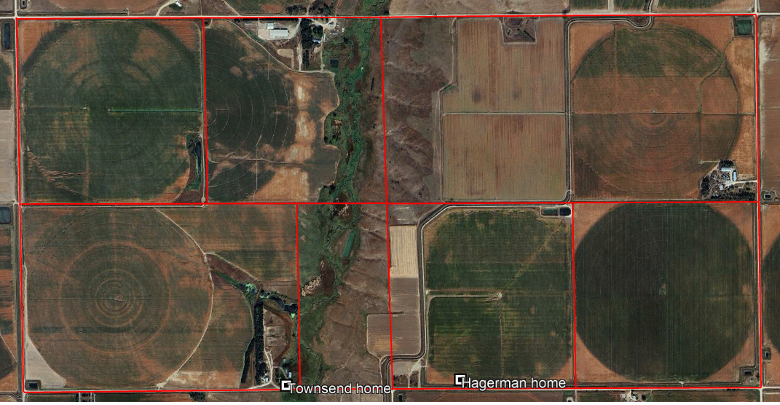

Who was this William Townsend, whose young son supposedly stumbled across the meteorite? He was John Hagerman’s neighbor: he owned the property on the West side of Hagerman’s farm, and a small creek called Sand Draw crossed through both properties. That’s the same Sand Draw where Hagerman had discovered the meteorite in 1903.

On February 28, 1908, the Ainsworth Star-Journal mentioned the meteorite for the last time. It was an odd article. Readers were finally given an explanation of how the meteorite was rediscovered: “the meteor was found on the W. G. Townsend place northwest of town last year by one of his little boys.” That is roughly consistent with the timeline laid out by the latter four articles and Winchell letter: the meteorite was missing in January 1907, and had been rediscovered by April, at the latest.

However, no mention was made of Uncle Johnny Hagerman or the meteorite’s prior history, and no explanation was offered as to how his prized possession could have ended up discarded, on his neighbor’s land: John’s home was located about 800 meters and across a creek from the property line he shared with the Townsends.

Was “the Hagerman meteor” really found dumped by the creek, on his neighbor’s farm? I don’t think it’s likely that a valuable object known to the entire town would have been so carelessly disposed-of.

Or, is there a chance that the child had stumbled upon…a new mass of the meteorite?

None of the articles suggest that as a possibility, and the article dated May 10, 1907, described the meteorite being brokered by Judge Toliver as “the Hagerman meteor.” The mass received by E. E. Howell weighed 23 1/2 lbs. When describing the specimen, Howell said, “A fractured surface on one of the sharp corners, and adjoining flat side, shows where perhaps two lbs. had been broken from the mass…” That lines up pretty well with Hagerman’s original find: twenty-five pounds, minus a few “chunks.”

I think it’s safe to say that the iron sold to E. E. Howell by the judge was John Hagerman’s “missing” meteorite.

As the agent brokering the specimen, Judge Toliver would have described the meteorite to interested parties like Newton H. Winchell and Edwin E. Howell. We know from the first Ainsworth Star article that the judge knew John Hagerman personally, and that he was intimately familiar with the meteorite and the tale of its discovery. But, in his correspondence with Howell, the judge seems to have neglected to mention that John Hagerman had found the Ainsworth meteorite years prior, and instead relayed only the story of the meteorite’s “rediscovery” on Townsend’s property.

And it seems as though the judge forgot to mention at least one other important detail to Howell. We need to finish that above quote from Howell’s description of the mass, published in the American Journal of Science:

“A fractured surface on one of the sharp corners, and adjoining flat side, shows where perhaps two lbs. had been broken from the mass antecedent to its burial, probably when it fell.”

But…we all know exactly when that corner was broken: Eli Sawyer removed it, and Judge Toliver himself had bought some of that, and had his paper knife made out of it. That detail must have escaped the judge’s memory when he was describing the mass to Howell…in letters he was writing at his desk, with the knife proudly displayed in front of him… Maybe the judge thought that detail wasn’t important…or maybe he didn’t want prospective buyers to think the meteorite might be “damaged”…

It’s also a bit weird that Howell’s published description of where the Townsend boy found the iron (which, again, must have been related to him by Judge Toliver) roughly matched the description of where Hagerman had found the meteorite in 1903. In both the Ainsworth Star-Journal and American Journal of Science accounts, the iron was found along “Sand Draw.”

I just don’t think the later story is plausible. We’re talking about something Hagerman coveted: he didn’t drag it almost a kilometer, across a creek, to a far corner of his farm, and chuck it over a fence before his tragic accident.

I’d like to believe that William Townsend legitimately acquired the meteorite from Hagerman’s brother or estate. Or that the judge might have carelessly omitted some details when communicating with Howell, or even deliberately simplified the history of the iron. But, in that case, why would Townsend and/or the judge also concoct an implausible story about how Townsend had acquired it? What was ultimately published wasn’t a simple omission, and it doesn’t make sense.

The odd “rediscovery” story does, however, conveniently establish Townsend as the sole legal owner of the meteorite. It would explain why John Hagerman’s estate and surviving brother, Calvin, didn’t own the specimen, and why he wasn’t entitled to a share of the $200 from its sale. …Or all of it.

Coincidentally, in addition to being an elected judge, J. C. Toliver happened to be an experienced local probate attorney. He would have known that Hagerman’s iron should have passed to his estate…and would have known exactly what kind of story would have been needed to get around that…

At this point, I’m fairly convinced that William G. Townsend — who, again, was John C. Hagerman’s next-door neighbor — somehow took possession of the iron after Hagerman’s accident. After seeing the January 18, 1907 article in the paper, he brought the meteorite to the attention of Judge Toliver. He and the judge agreed to split the proceeds of its sale, and the judge helped to devise a story that would grant Townsend clear ownership. We know the judge had found the meteorite interesting enough to purchase a piece of it years prior, he knew it was valuable, and he arranged the sale of the iron as soon as it was “rediscovered.” The judge also appears to have ensured that the original finder and rightful owner, John C. Hagerman, was scrubbed from the published history of the meteorite.

There’s admittedly a lot we will probably never know for certain about the situation, but I don’t see a better explanation given the timeline and published information.

Fishy business!

If anyone might have any additional correspondence or information that might help to shed more light on this story, please reach out. Unfortunately, E. E. Howell was a private meteorite collector working with Henry A. Ward in Washinton D.C. at the time: his correspondence doesn’t seem to be preserved in an institution like the Smithsonian or AMNH. I don’t know if Judge Toliver’s correspondence might be preserved in Ainsworth or elsewhere.