irons

Iron meteorites can be divided into two main groups: those that formed in the cores of large differentiated bodies, and those that didn’t. For an explanation of differentiation, see the “achondrites” page.

Recent work has shown that some iron meteorite groups may have formed at roughly the same time as CAIs – some of the earliest solids in our Solar System. Some irons preserve isotopic evidence from the early solar nebula no longer present in other meteorite groups.

So, while chondrites may be more primitive in that they appear to represent direct solar nebula condensates, the parent asteroids and planetesimals of iron meteorites may predate the rocks we classically consider to be the oldest, most pristine meteorites.

While irons are secondary in that they must have formed from the melting and/or differentiation of large asteroids made of precursor nebular / chondritic material, it seems that they formed right around the time of most chondrule/chondrite formation. In other words, irons may have formed from older chondritic parent bodies, and the chondrites we know today may have accreted later.

Amazingly enough, we have enough samples from a few groups of irons that we are able to trace their parent cores’ solidification. Different elements have different chemical tendencies. Some elements prefer to remain in a metallic melt, some prefer silicates. And some prefer to crystallize out in solid metal while a core is crystallizing, and some prefer to stay in the liquid metal. Here’s a great paper showing how the compositional evolution of irons can be traced through the bigger iron meteorite groups: Fractionation trends among IVA iron meteorites: Contrasts with IIIAB trends, by J. T. Wasson and J. W. Richardson (2000).

Since irons account for 8-10% of meteorites found around the world, and they’re often found as very large, crater-forming e larger than stones, they have typically been viewed as relatively common meteorites.

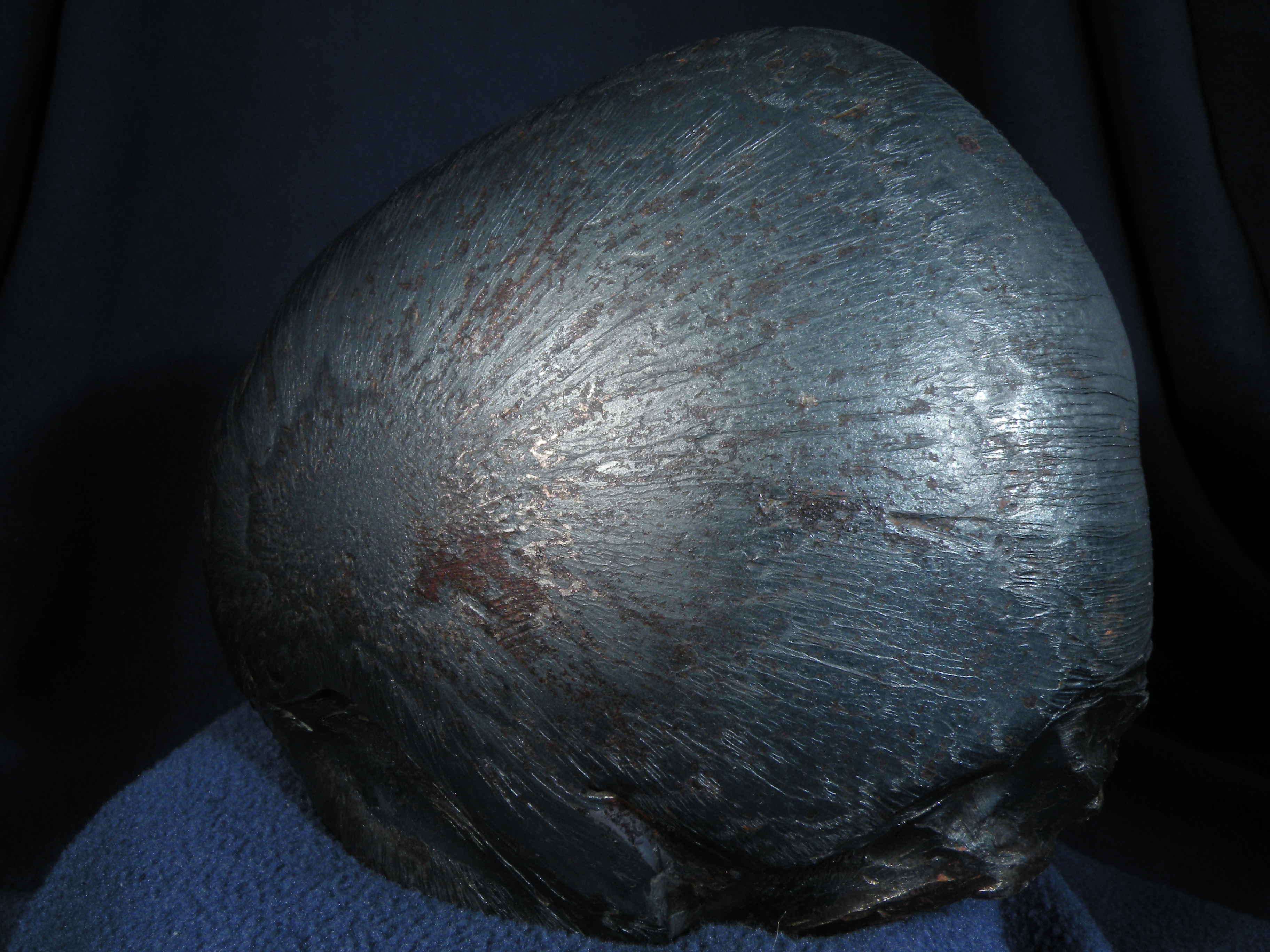

But, in places where people have systematically searched for meteorites (Antarctica, Northwest Africa, Oman), irons account for a mere 1-2% of finds. If witnessed falls are taken into account, irons are extremely rare. They’re unusual, they’re visually stunning, and they tend to withstand both weathering and ablation much better than stones do, resulting in meteorites with very aesthetic shapes.

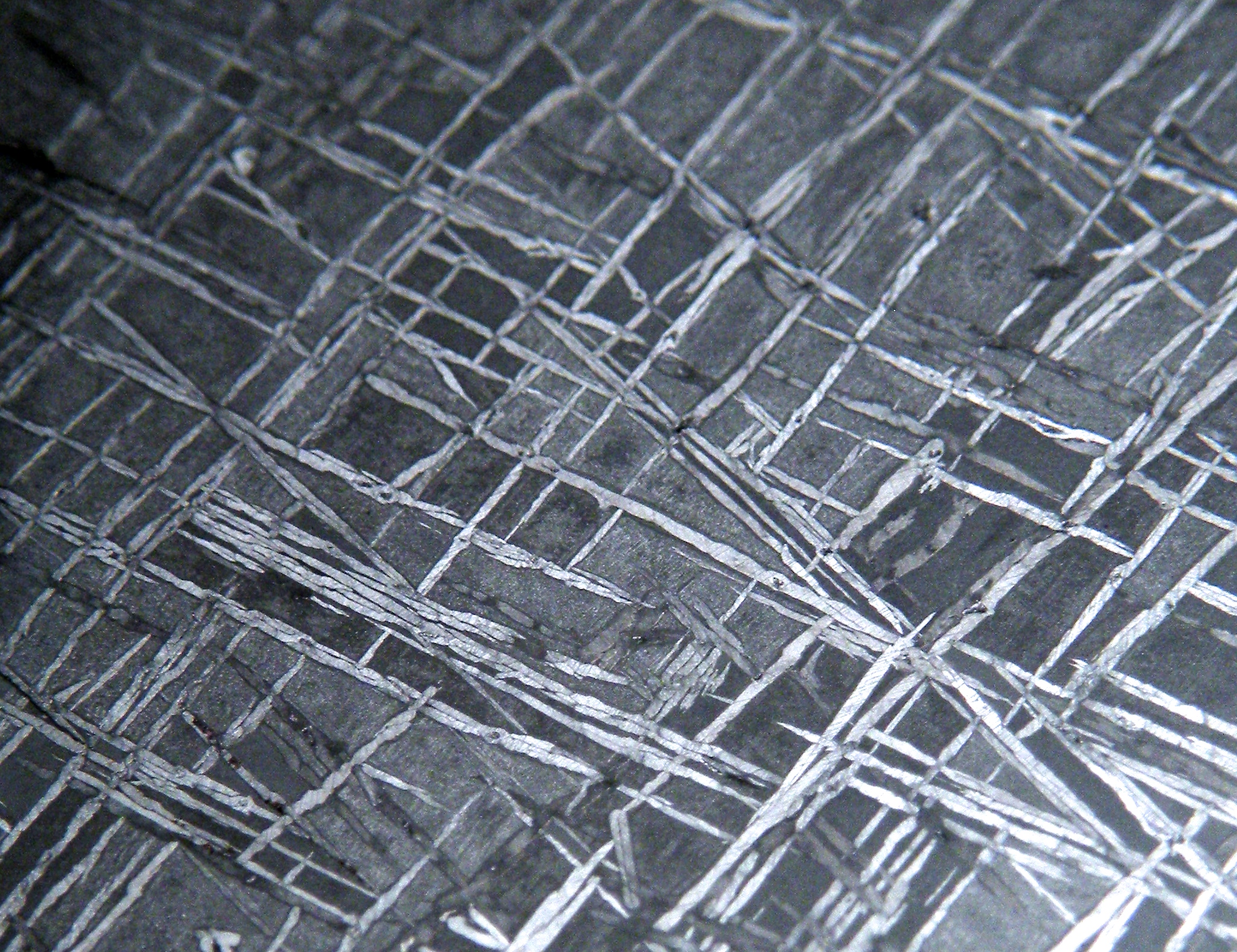

Perhaps the most visually intriguing thing about iron meteorites is that most of them display a remarkable internal crystalline structure most often called a ‘Widmanstatten pattern,’ or ‘Thomson structure’ — most people refer to it with the former name, but Thomson’s discovery of the structure predated Widmanstatten’s by a few years. It was unfortunately published in a French journal and escaped notice until many years later.

The details regarding the formation of the structure are complicated and somewhat technical, but the basics are as follows:

1) The starting material is molten Fe-Ni mixture.

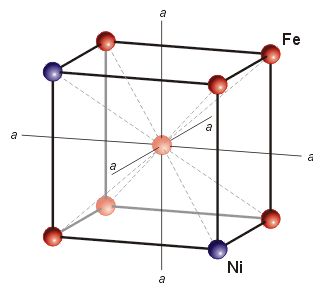

2) This mixture solidifies at ~1500°C and starts out in a particular atomic arrangement called taenite.

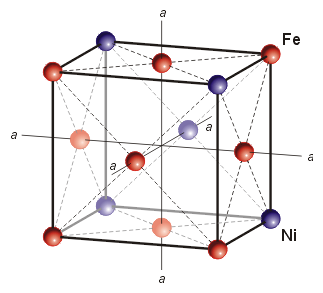

Taenite Unit Cell, image from

Jan & Wadi Woreczko

3) Between 1500° and ~723° the solid Fe-Ni mixture slowly rearranges itself atomically to a different structure called kamacite (the amount that changes depends on the amount of Ni present in the mixture as well as the cooling rate and impurities that facilitate nucleation and growth).

Kamacite Unit Cell, image from

Kamacite Unit Cell, image from

Jan & Wadi Woreczko

4) After it cools beyond ~720°, the atoms lack the kinetic energy needed to rearrange themselves and the pattern stops forming.

The key thing to note is that step three needs to occur over, at the very least, tens or hundreds of million years in order to give the atoms in the mixture enough time to rearrange themselves into the new crystal structure. The cooling rate of the solid Fe-Ni mixture must be at most tens or hundreds of degrees per million years in order for a Thomson structure to form.

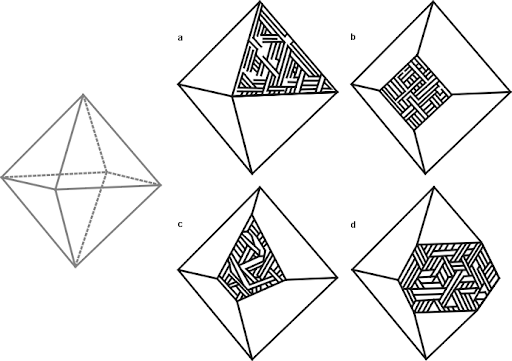

So, what do you see when looking at a cut and etched iron? Most meteorite-enthusiasts would tell you that what you’re seeing is an intergrowth of kamacite and taenite. That’s mostly true. The octahedral structure that is seen in most iron meteorites forms because the kamacite preferentially nucleates and grows along the taenite’s octahedral crystal structure. They don’t “grow together” — the kamacite grows at the expense of the taenite. And, usually, the vast majority of what you’re seeing is kamacite. Usually. High-nickel meteorites (e.g. most ataxites) are made entirely of taenite.

If you’re interested in what exactly goes on in the process, I would explore online — try here or here for a few good open-source papers.