chondrites

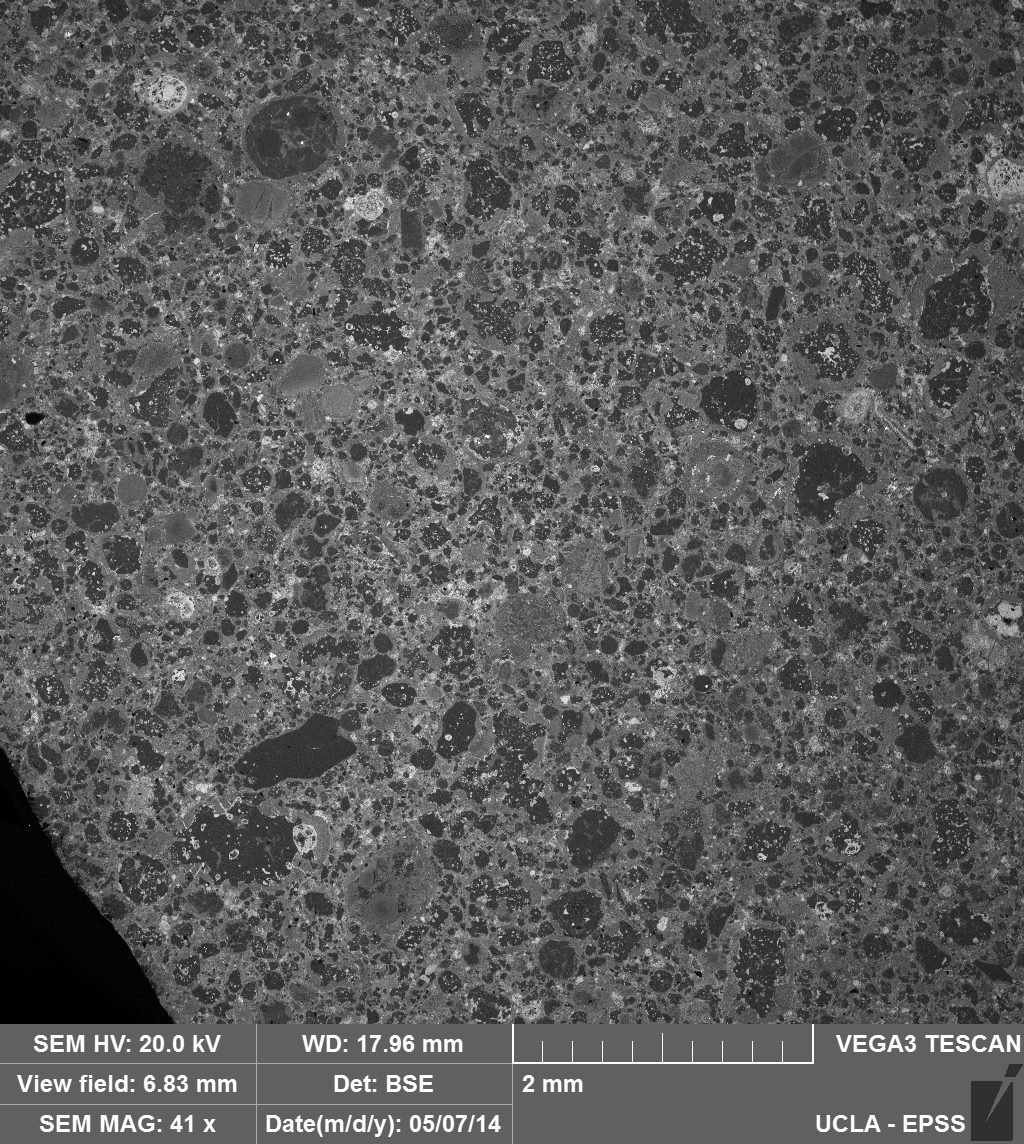

Chondrites are the most primitive group of meteorites. They have formation ages dating to at least 4.56 billion years before the present, and have been little changed since then. They are called chondrites because they contain structures called chondrules: small, spherical droplets of rock that condensed in the solar nebula via still-debated and little-understood processes.

Chondrites are the most primitive group of meteorites. They have formation ages dating to at least 4.56 billion years before the present, and have been little changed since then. They are called chondrites because they contain structures called chondrules: small, spherical droplets of rock that condensed in the solar nebula via still-debated and little-understood processes.

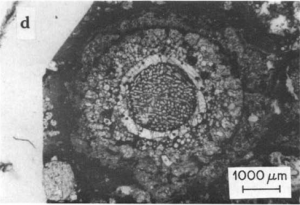

Chondrules are enigmatic. They are high-temperature droplets of silicate minerals such as olivine, pyroxene, and feldspars; they were heated to ~1,500+°C, and then quenched in a matter of minutes. Some chondrules exhibit concentric layering; up to five melting/depositional events have been observed in single chondrules. So, whatever formed them was (sometimes) cyclic or repeating in nature.

Yet the matrix surrounding chondrules formed at temperatures closer to 800°C. How the repeating, extraordinarily high temperature events that formed chondrules occurred is still unknown. Current hypotheses are that chondrules are:

1) direct condensates (e.g. from a superheated nebula, as it cooled)

2) the product of lightning propagating through nebular dust

3) produced by the gravitational or pressure bow-shock waves of planetesimals, or

4) the product impacts (condensed droplets of rock vaporizes in impacts).

I might have missed a theory or two, but those are the ones that come to mind.

Chondrite nomenclature is pretty easy to understand once you get the hang of it.

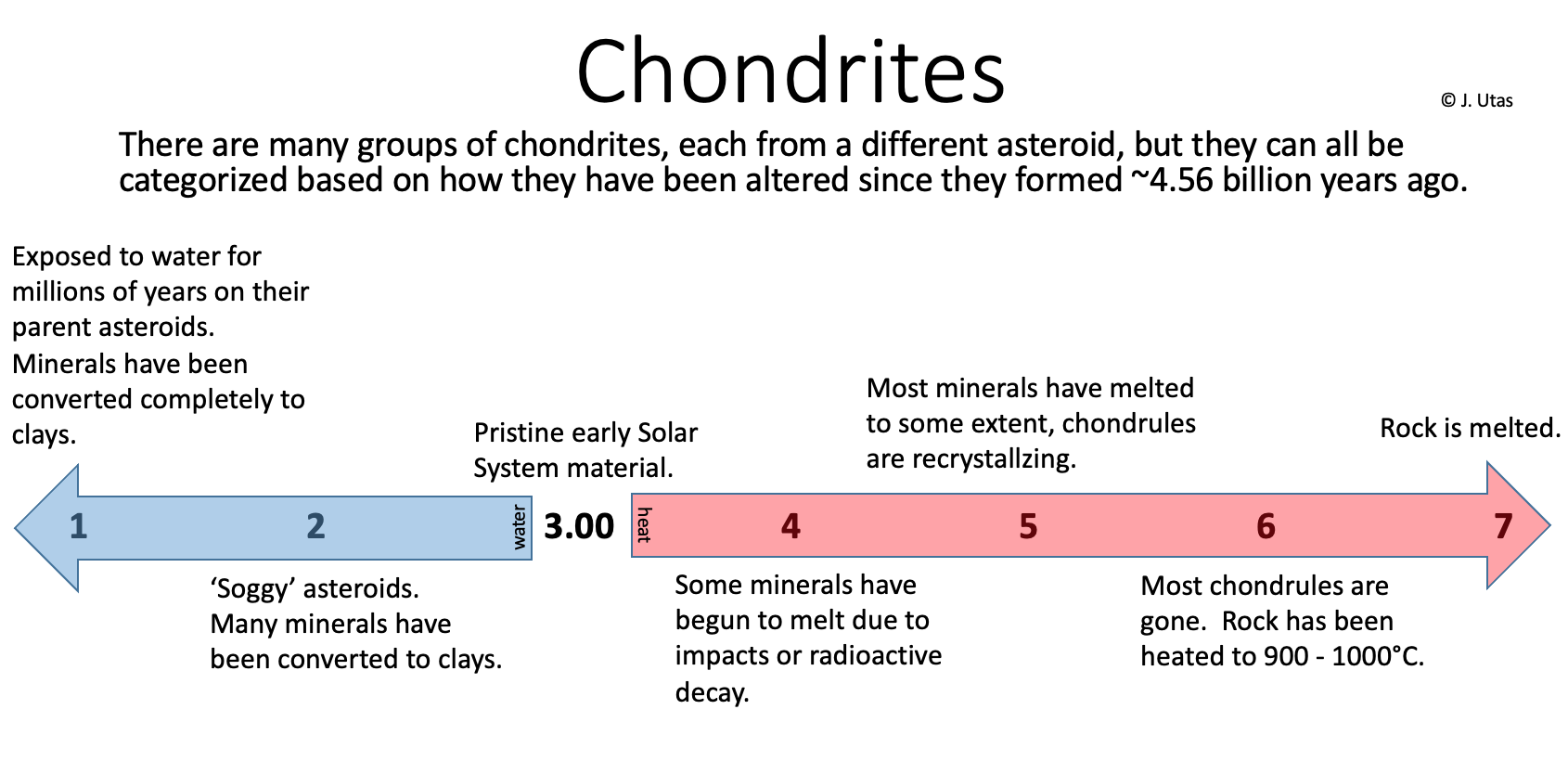

The first letter(s) in the classification denote a group of meteorites determined by chemical differences. The number following the letter(s) determines the nature and amount of alteration that the meteorite has undergone since its chondrules first solidified.

A type-3.0 chondrite would be essentially unchanged since forming. The higher the number (3.0 to 6), the more (re)melted the chondrules get, until you can’t see them anymore. Past 6 or 7 (it’s debated as to whether type-7 chondrites are a legitimate thing), you wouldn’t be able to see the chondrules anymore and you would have a ‘primitive achondrite.’ Aka, a melted chondrite, with no visible chondrules.

If the number is less than a 3, the meteorite wasn’t heated/melted, but was instead altered by the presence of water into clay minerals (likely at temperatures at which liquid or frozen water would be stable). Some type 1 and 2 meteorites have *never* been heated above ~150°C since forming. That’s 4.557 billion years of cold storage in some cases.

In other words:

Many meteorites are simply classified as “3,” in which case we laymen don’t know whether the meteorite in question is a 3.01 (really primitive!) or a 3.9 (less primitive). Type “3” stones can be anything in that range. Sometimes, analyses contain enough data to tell.

“Ordinary” chondrites are more common than most others, and include H, L, LL, and arguably HH chondrites. It’s important to remember that these “common” classes still include some of the least altered — and thus most interesting — types of meteorites.

Carbonaceous chondrites are the most-studied meteorites because they often contain evidence of water and complex organic molecules — stuff necessary for the formation of life. It has been hypothesized that these meteorites may have ‘seeded’ earth with the compounds required to create the most primitive organisms.

Other types of chondrites include R, CH, CB, K, EH, EL, and others.

Current science suggests that these chondrites are samples from different parent bodies — rocks that formed in different regions of the Solar System, as they are chemically and/or isotopically distinct from other meteorites. These classes account for no more than a percent or two of all recovered meteorites and are extremely rare and of relatively high scientific importance.