What do meteorites look like?

Maybe you’ve just found a strange rock, or maybe you’ve had one laying around for years. Maybe someone has approached you with a rock they think is a meteorite, hoping to sell it.

How do you figure out what it is?

That’s a tough question. There are many different types of meteorites, and an even wider variety of rocks from Earth. But there are a few things you can look for.

Freshly Fallen Meteorites

When meteorites enter the atmosphere, they’re moving really quickly. Usually ~ 20 to 40 kilometers per second. For comparison, the Space Shuttle used to enter the upper atmosphere at ~8 kilometers per second.

This causes intense heat and pressure to act on the surface of the rock. The outside of the meteorite vaporizes, and a thin molten layer forms on the outside of the rock. The body is usually broken up by extreme ram pressures, and the fragments begin to ablate as well.

If any rocks do survive the passage, they almost always bear some scars. As the fragments are slowed down by the atmosphere, their surfaces begin to cool. The last molten material on the rock’s surface cools and solidifies on the outside of the meteorite, forming a “fusion crust.” This layer is usually fairly smooth, but is not the polished texture of a water-worn pebble.

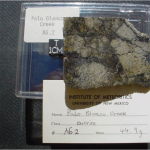

Freshly-fallen meteorites as found:

As you can see, the ~black outer layer is usually ~smooth, but finely textured. While meteorites themselves almost never contain any bubbles, the outer layer of crust can exhibit small bubbles (but usually doesn’t). Note that none of these rocks has actually melted through. Inside, they’re still grainy rocks, for the most part. See here, #2 for a little more information on what happens as meteorites fall to Earth.

2) Most meteorites start out on a gradient from ~white to ~black inside. Here are a few examples:

Freshly fallen meteorites, naturally broken and cut:

The above album contains freshly-fallen meteorites. Some are broken, others are cut. Most of the broken stones fragmented in the atmosphere or when they landed on a hard surface. As you can see, they range from ~light grey to black inside. There are a few other details you might have noticed…a few have started to oxidize (3rd, 6th images). More on that later.

There are also a few exceptions to the grey-black gradient — namely with pale green meteorites made mostly of olivine or pyroxene. However, these meteorites are exceedingly rare, and only a dozen or so have been seen to fall in recorded history. So, we’ll skip the details on diogenites and visually ~similar meteorites.

So, right after they fall, most meteorites have a black crust on the outside, and they range from ~white to ~black on the inside. But most meteorites that are found didn’t fall recently. Most meteorites found on Earth have spent thousands of years here, just waiting to be picked up. What do those meteorites look like? Well…

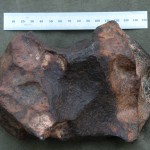

Weathered meteorites

~95% of meteorites contain between ~10 and ~20% metallic iron when they fall. This iron begins to rust after landing on Earth: a freshly fallen meteorite won’t be rusty, but ~95% of meteorites will begin to show at least minor oxidation within weeks to months. After a few decades, they’ll be ~thoroughly rusty. Most meteorites on Earth fell at least hundreds if not thousands of years ago, so a rusty color is fairly typical of most meteorites:

So…rusty rocks. If you look carefully, you can see that some still have some smooth fusion crust, although it has been weathered to brown or has been mostly chipped off in many cases. The textures are important — note that the older fusion crust is uniformly textured even on concave surfaces: that’s uncommon for terrestrial rocks. Weathering on usually Earth starts from the edges/corners, rounding those off first.

Other Defining Characteristics

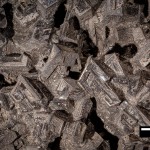

There are a few other details you can look for. ~90+% of all meteorites are “stony” meteorites. This kind of meteorite usually contains features called chondrules.

What are chondrules? We’re not sure exactly how they formed, but we know they date back to the earliest days of our solar system, 4.56 billion years ago. In a nutshell — they’re small, spherical droplets of rock, usually about a millimeter across. They can range from 0.1 mm or smaller to ~1 cm across. In rare cases they can be larger, but they’re usually 1 mm or so. Here are some examples of chondrules in cut meteorites:

~90% of meteorites will look something like this when cut. When looking for meteorites, this is what you are most likely to find. Note that in many cases the chondrules are only faintly visible, or they may be almost absent: this is common. Also, note that many of these stones exhibit visible iron-nickel flakes when cut. A more oxidized meteorite might not have any of these left, but a polished stony meteorite will almost always still have some of these. Flecks of specular hematite in terrestrial rocks can look similar, but appear darker, and less like native metal.

Also – shock veins. When asteroids collide with each other in space, they usually do so at thousands of miles per hour. Some become truly broken up and brecciated, while others get only a few thin, usually black, veins of melt. Here are some examples:

Not all meteorites have these, but they can be a good indicator. Some terrestrial rocks can look similar, but they’re not too common. Terrestial volcanic breccias and fault breccias do exist, though. They’re one of the more common meteor-wrongs I get sent pictures of, because they grossly resemble Lunar meteorites.

Stony meteorites without chondrules (achondrites) are very rare, and they usually look very much like terrestrial igneous rocks on the inside. The only good identifying feature of this type of meteorite is fusion crust, and possibly shock veins. These meteorites usually don’t contain much iron and will rarely rust or oxidize over time. In ~20 years of hunting in good desert terrain, we have found several thousand chondrites, and just a few of these uncommon meteorites. They’re so rare — and usually so hard to identify — that it’s probably not worth spending time looking for them until you know quite a bit about meteorites. Here are some examples.

Iron and stony-iron meteorites are very rare, but are relatively easy to recognize. These classes make up ~2% of meteorites, and they are mostly metallic.

All of the above meteorites would be very strongly attracted to a magnet. As much as a piece of solid iron. Note: many have deep indentations in their surfaces, but no “bubbles.”

But be careful — many terrestrial rocks also contain (magnetic) iron, and people have been concentrating iron to make tools (and thus, slag), for thousands of years. Most iron-bearing, magnetic rocks on Earth are from Earth.

Which raises an important idea: if you want to hunt for meteorites, it’s a good idea to familiarize yourself with your local geology, and characteristics that meteorites do not have. Many meteorites have been recognized by people who knew nothing about meteorites: they were just familiar with their local geology, or the “normal” rocks on their farm, and they noticed a rock that looked out of place.

Knowing what meteorites look like is really only half of the battle. If you want to find a meteorite, a general understanding of geology is very helpful. If you learn as much as you can about different rocks and how they form, you will be much better equipped to identify rocks (and meteorites) in the field.

Common Meteor-Wrongs

Here are some photographs of pieces of a very common meteor-wrong — man-made slag. These are not meteorites:

Image credits: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12.

Note the bubbles, large, ropy flow features, and “skin” that often forms on the surface of pooling slag. Meteorites don’t “melt-through” when they’re coming through the atmosphere, so if you see characteristics that suggest your rock was literally flowing or molten like lava, you know it’s not a meteorite. The molten surface of slag is very different in texture from a fusion crust (compare to other images above), and there are usually large bubbles below this smooth skin.

One or two of the above specimens don’t look half bad. The 7th image in particular isn’t a bad wrong, but the few included flint fragments suggest it’s not a meteorite — a few pieces of unmelted rock appear to have been incorporated into the molten metal. Small amounts of sand and rock can adhere to a rusting meteorite though; this can give a grossly similar appearance, so be careful. I’d probably suggest cutting a specimen if in doubt. If you see vesicles or vugs, you’re almost certainly out of luck.

Here’s a great page by Helmut Föll on furnace bloom, how it’s made, and why it looks how it does. And a stable PDF of the page, saved May 2018.

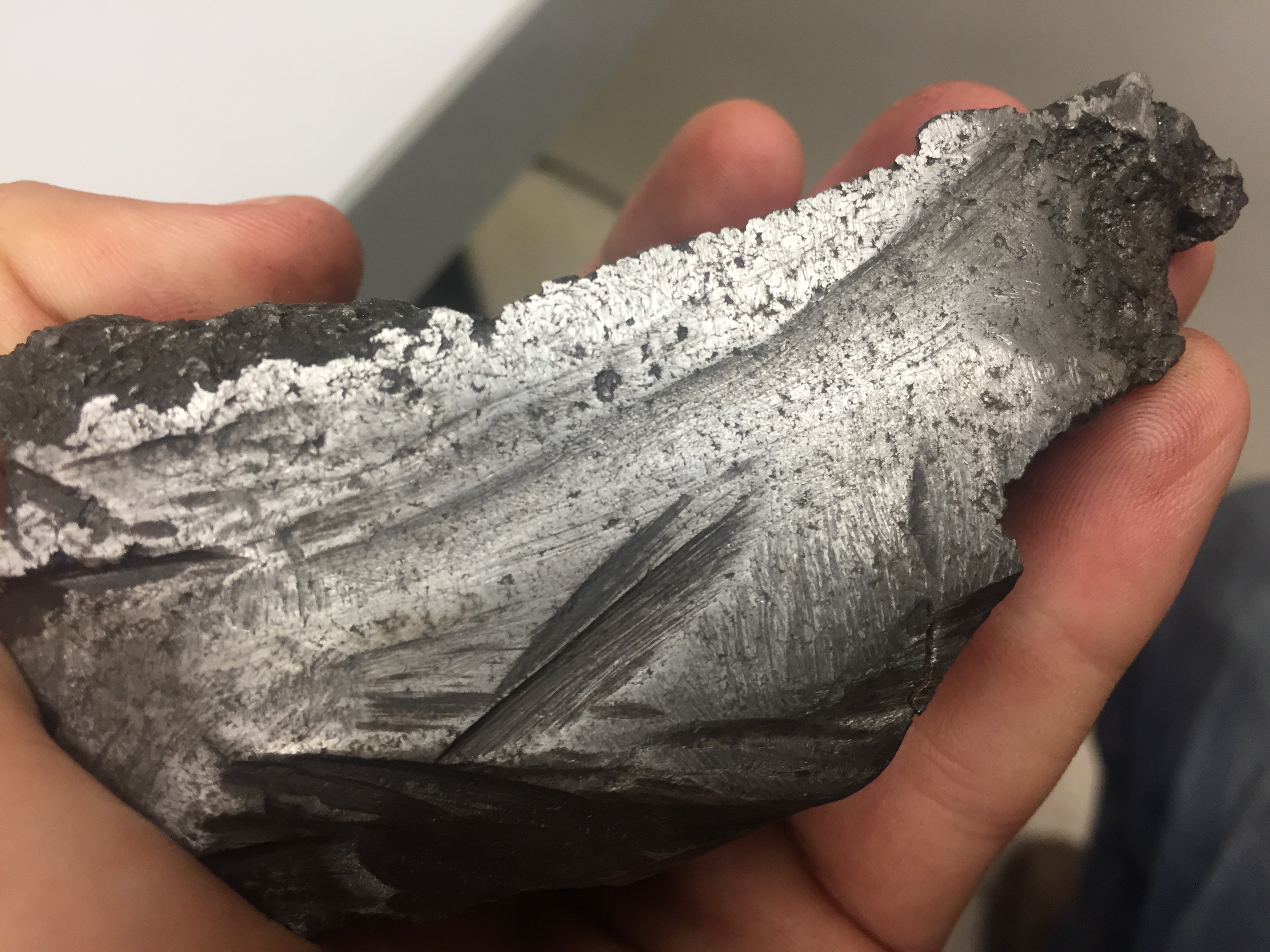

Another common wrong — man-made ferromanganese (source):

Ferromanganese is a component of steel manufacturing. It is commonly found along railroad tracks in the US (so, just about everywhere), and I’ve had a few photos of it sent in from elsewhere around the world. Many old rail lines have been reclaimed, are overgrown, and are no longer visible.

Ferromanganese feels quite dense, is often ~a little magnetic, looks silvery/metallic when chipped or cut, and has a rusty-to-black exterior that often rubs off on your fingers as a fine black dust.

How can you tell it from a meteorite? The surface of manganese slag specimens is often quite rough, but not very rusty: that fine black dust that’s hard to get off of your hands is manganese oxide, and it looks very different from typical iron ‘rust.’

An iron meteorite would be made of ~90% iron, and would be very strongly attracted to a magnet. All metallic meteorites are strongly magnetic. Most manganese slag isn’t very magnetic. While manganese is dense/feels like metal, it’s usually not strongly attracted to a magnet. Some manganese slag contains a decent proportion of iron, though, so a magnet isn’t a perfect discriminant. Some samples may require a chemical analysis to tell for sure.

Why can’t a meteorite be made mostly of manganese, aluminum, copper, or some other metal? Earth is geologically and hydrologically one of the most active bodies in the Solar System — second, perhaps, only to Jupiter’s sulfur-rich moon, Io. Complex hydrologic reactions have taken place on Earth over billions of years, concentrating these elements, and we are fairly certain that this has not happened anywhere else in our Solar System. You need large amounts of liquid water carrying acids or bases in addition to extended exposure to geothermal heat to drive the kinds of chemical reactions that can concentrate, say, copper. The few bodies that have enough geologic heat to drive these kinds of reactions, like Io and Venus, are bone dry, and the few bodies with enough water to support these kinds of reactions, like Europa and Enceladus, are extremely cold. Earth is a pretty unique place in the Solar System.

Most iron meteorites formed by a very simple process: chondritic material was melted by heat from impacts or heat released by the radioactive decay of elements, and the heavy stuff sunk to form a metallic core. The metal in most chondrites is ~85% iron, and ~15% nickel. There’s ~no natural way to concentrate large amounts of, say, manganese, copper, or other metals in such a process. You can, in rare cases, find *micron*-sized inclusions of copper and gold in highly-shocked meteorites. That’s as far as these kinds of “concentrating” systems ever got, out in space.

Conversely, in additional to natural geological processes on Earth, metals have been concentrated by people, on Earth, from prehistoric times up to the present. Most pieces of metal brought into labs as possible meteorites are industrial waste. Which makes sense — people have been refining different metals for thousands of years, and leaving the trash just about everywhere. I’ve found slag on mountainsides, in farm fields, and poking through pine needles in remote forests. It’s everywhere.

Here’s a good example.

Some folks brought this piece of metal into UCLA in 2018. They managed to hack it off of a massive, ~rounded mass of iron they found in a wash in a very remote part of the Mojave Desert. The thing they found was over a meter across and weighed at least a few tonnes. The photos of it looked kind of like a meteorite, but the cut surface looks…dendritic. And UCLA’s SEM showed that the metal was almost pure iron with trace amounts of silicon and carbon.

Some folks brought this piece of metal into UCLA in 2018. They managed to hack it off of a massive, ~rounded mass of iron they found in a wash in a very remote part of the Mojave Desert. The thing they found was over a meter across and weighed at least a few tonnes. The photos of it looked kind of like a meteorite, but the cut surface looks…dendritic. And UCLA’s SEM showed that the metal was almost pure iron with trace amounts of silicon and carbon.

It was cast iron. I have no idea how it got where they found it, but it is what it is.

Here’s another odd example.

Someone sent me photos of this thing in early 2019, claiming that it was a meteorite. The large curved broken faces pretty much ruled that out. It was a piece of brittle, granular metal. Slag often breaks that way. Metallic meteorites almost never do.

The finder said that a portable XRF gun analysis had showed that it was comprised of 99.9% iron. That’s really pure iron. More pure than has ever been found naturally on Earth or anywhere else. So pure that it must have been refined artificially…

The analysis actually showed ~98.7% iron, with trace amounts of manganese and chromium, and around 0.1% nickel. I don’t know the name of the exact alloy, but that’s a pretty typical composition for man-made steels. Both Mn and Cr improve a steel’s durability, and Cr helps to inhibit corrosion. The person later listed it on eBay for $100,000 as a specimen that, I quote, “baffled all experts”…

In general: if you have a strange piece of metal, or a metallic rock, and it’s not strongly attracted to a magnet, it’s not a meteorite. There are no exceptions. If you have something metallic, and it’s not magnetic, it’s probably man-made.

And if you find something that’s iron, but contains less than ~4% nickel, it’s probably man made, and definitely not a meteorite. There are rare exceptions, and I might make a page about them at some point, but unless you live in Kassel, Germany, or on a remote island off the West coast of Greenland, you don’t have to worry about it.