Central Missouri (Ainsworth), IIAB

This specimen was a very fun mystery to unwind. It’s a bit of a story, and I thought folks might like to see the kind of research that can go into identifying a mislabeled specimen.

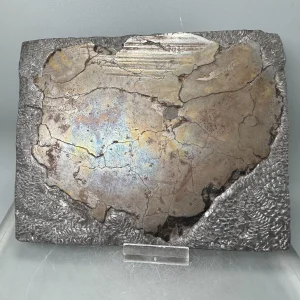

This is what I had to work with:

The slab apparently turned up in an old mineral collection in late 2024, and I came across it listed for sale online as a slice of Toluca. Toluca was a widely distributed iron meteorite back in the late 1800s and early 1900s, so that ID was historically plausible given the “1850” label.

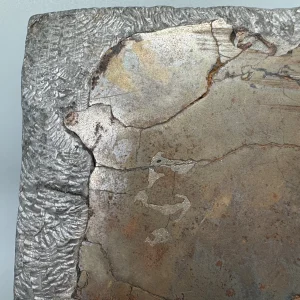

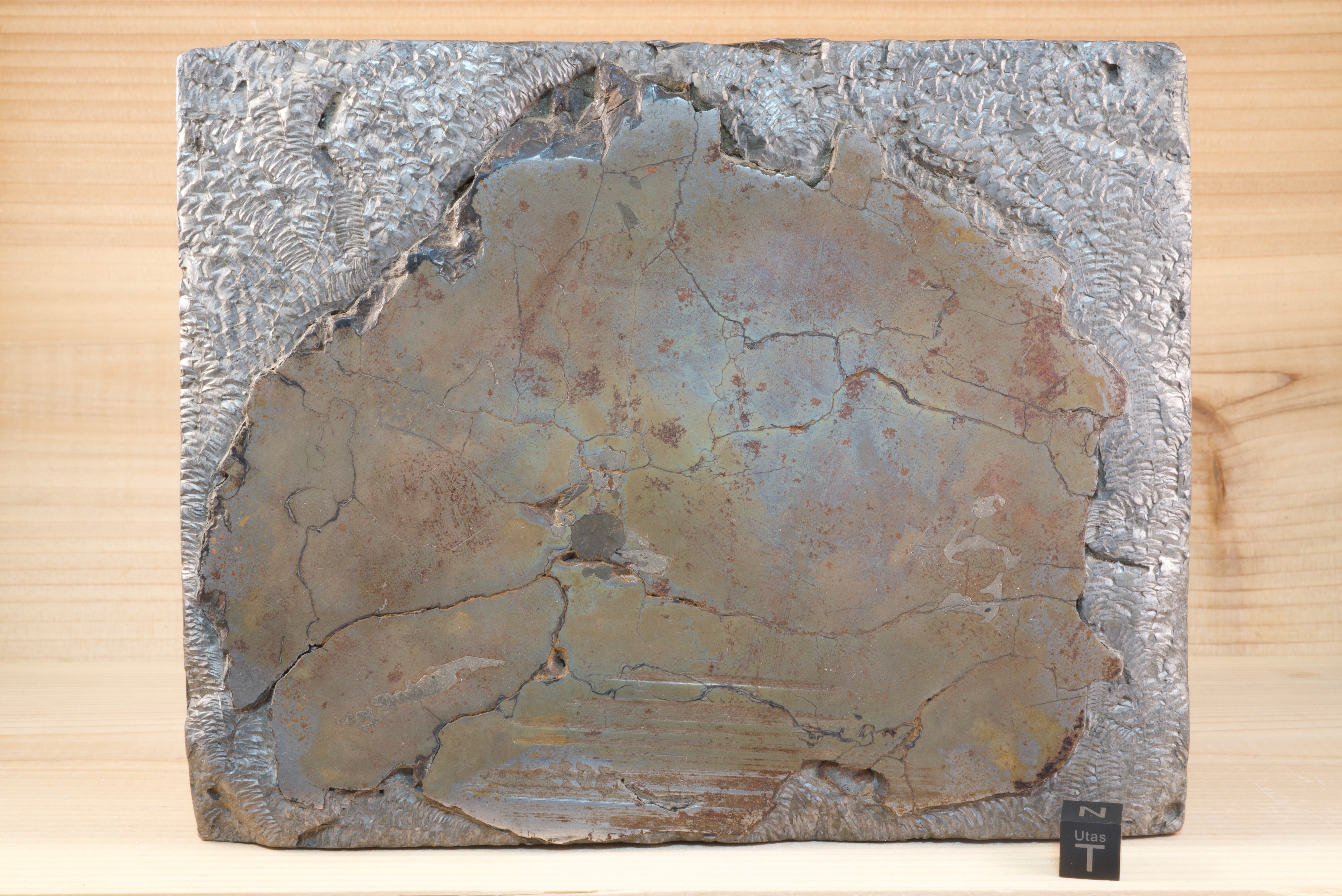

But, Toluca is a IAB, and a coarse octahedrite. The pattern visible in the cut face of this mystery slice is a textbook coarsest octahedrite, similar to some IIAB irons readily available today like Agoudal and Sikhote Alin. Given the proportions of the pattern and the large, graphic schreibersite inclusions, this slice had to be a IIAB, not a IAB – it couldn’t possibly be Toluca.

What the heck is it?

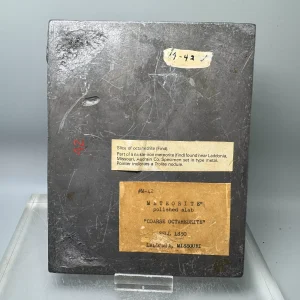

The way this specimen was labelled and mounted in typeset metal (!?) suggested that it was almost certainly an older, historic find. But, the location given on its labels – Laddonia, Missouri – didn’t ring any bells, and searching the Meteoritical Bulletin for irons from Missouri didn’t turn up any likely matches. So, it was either a mislabeled piece of a known meteorite, a piece of a “new,” undocumented iron, or…?

At that point, I reached out to the seller to try to get it. I didn’t know what it was, but if it was an older IIAB, it didn’t really matter. The labels looked old, it looked really cool — kind of like Han Solo frozen in carbonite in its odd backing — and…there had to be some way to figure out what it was. IIABs aren’t common, and there simply weren’t very many meteorites known and described by the ~1850s…

The search began in earnest.

“There are known knowns…”

What did I know for sure? Based on the cut face, it was a IIAB – and not a hexahedrite. That’s good, concrete information: I knew what class it was, and should be able to quickly rule out about half of known IIABs just based on their structure.

Beyond that: it didn’t match anything published from Missouri. If I assumed the find location and/or discovery date might be wrong…which seemed likely…I might have to go through every IIAB in the Meteoritical Bulletin.

So I decided to cover all of my bases and just start with that. I searched the online Meteoritical Bulletin Database for IIABs, sorted by year, and looked each one up in Buchwald’s Handbook of Iron Meteorites. I checked every IIAB found through around 1920. There were a few widely-distributed coarsest octahedrites available in the late 19th / early 20th centuries: São Julião de Moreira, Mount Joy, and Ainsworth were probably the most likely. But, none of those were from Missouri, and nothing really stood out.

At this point, I was getting less optimistic about my chances of identifying this thing. It looked as though at least some of the information on the older labels was either wrong, or this was a piece of an undocumented meteorite.

“But there are also unknown unknowns…”

After reviewing my notes, there were no obvious matches in the online Meteoritical Bulletin Database / Buchwald. At best, I figured that I’d now be hoping to match up the painted catalog number on it with a published catalog. Not promising.

The red number “42” on the back of the slab looked like some of the painted numbers I’d seen on old Charles Upham Shepard and Field Museum specimens. I thought I might also have recalled seeing similar neatly-scrawled red numbers like that painted by the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris…and maybe on some Albert E. Foote specimens… It was a long shot, but maybe I could find a specimen of a distributed IIAB / coarsest octahedrite with roughly this weight listed as “42” somewhere… Many older catalogs also include written descriptions of specimens, so if a “mounted” IIAB slice came up as a #42 somewhere, I might be able to figure it out? Time to start going through old catalogs…

Farrington’s 1916 Catalogue of the Field Museum Collection had a few specimens of Bacubirito listed as #42. Unfortunately, he correctly described that meteorite as a finest octahedrite, which is about as far as an iron could be, structurally, from a coarsest octahedrite. No luck there.

But, if you look at the meteorite descriptions in that catalog, individual specimens received very different catalog numbers than the “meteorite numbers.” For example, look at the above image: Bacubirito is #42 in the collection list / left-hand column, but that find includes specimens logged as “Cat. No. 1124” and “Cat. No. 537.” This catalog wasn’t text-readable, so I had to read through it to find “Cat. No. 42” on page 252: a 653 gram slice of Coahuila, a IIAB…

Coahuila’s a hexahedrite, and there’s no way Farrington would have confused that with a coarsest octahedrite. ~Close, but wrong. It was 2 AM. With no good leads, I called it a night.

…I found myself staring at a dark ceiling a little after 5 AM. I wasn’t getting back to sleep. One of the next catalogs I checked was F. W. Clarke’s Catalogue of the Smithsonian’s Collection as of November 1, 1886. It listed an 850 gram slice of Toluca labelled as #42. I think this entry could be why the seller identified this specimen as Toluca, but don’t know for sure. Regardless, one of the few facts we knew from the start was that this slice couldn’t possibly be Toluca…so, if this mystery slice was the slice labelled as #42 in that catalog, it would have already been mislabeled by 1886. But that wouldn’t make sense given the non-Toluca labels currently glued to the back of the piece.

That catalogue also had a supplement for the Charles Upham Shepard Collection the Smithsonian had recently acquired. #42 listed in the addendum was a 124.5 gram specimen of Union County, Georgia.

Union County is an interesting meteorite: a rare IC iron described as a coarsest octahedrite (!!), found in the early 1850s (!!!). The structure of the meteorite and the timing lined up pretty well with the old labels on the mystery slice, but Georgia’s pretty far from Missouri. And Union County is a structurally heterogeneous iron, with zones that could be variably described as coarse or coarsest octahedrite. Being a IC, it also lacks the large, graphic schreibersite crystals ~diagnostic for IIAB coarsest octahedrites, and which are very apparent in this mystery slice. It couldn’t be a match. Another dead end.

The search continues…

After that, I went through I don’t know how many more old catalogues, and looked up many, many more meteorites. Eventually, something caught my eye in this 2001 catalogue of the Vatican Collection. It wasn’t even part of the catalog, I was just skimming the written introduction:

Central…Missouri…1855…? What if…?

Just like that, the pieces fell together. A quick search revealed that two or three paired IIABs had been found in the general vicinity of what was then the young state of Missouri:

“Central Missouri”

A mass of “about 25 kg” was found sometime in the 1850s. Unfortunately, the iron was formally described around 50 years after it was found, in 1900, and almost no details of its discovery were preserved. Buchwald also noted, “at this time “Missouri” was a loose term including the states of Kansas and Nebraska, which obtained status as Territories in 1854 and became states in 1861 and 1867, respectively , it will be understood that the exact locality is unknown.” At the time, most of the land North and West of the young state of Missouri was completely unincorporated – not even “territories,” and the then-borders of the state were different than what you would see on a map today.

“Ponca Creek” or “Southeast Missouri”

A mass of “about 100 lbs” was found around 1860 or 1863 in or near what was then the Dakota Indian Territory. Again, location information for this find was quite limited: “It was found on the surface of the ground, in the Dakota Indian Territory, ninety miles from any road or dwelling.” The Dakota Territory was created in 1861 by President James Buchanan, and included what are now the states of North and South Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, and some of Nebraska. So that above statement is…not very specific. Some specimens of Ponca Creek were also catalogued as “Dakota”, “Dakotah”, “Dacota”, etc., named for the territory. More on this mass below.*

“Ainsworth”

A mass of about 25 lbs, “found in 1907.” This is the only mass for which we have good location information: it was found about six miles Northwest of Ainsworth, Nebraska.

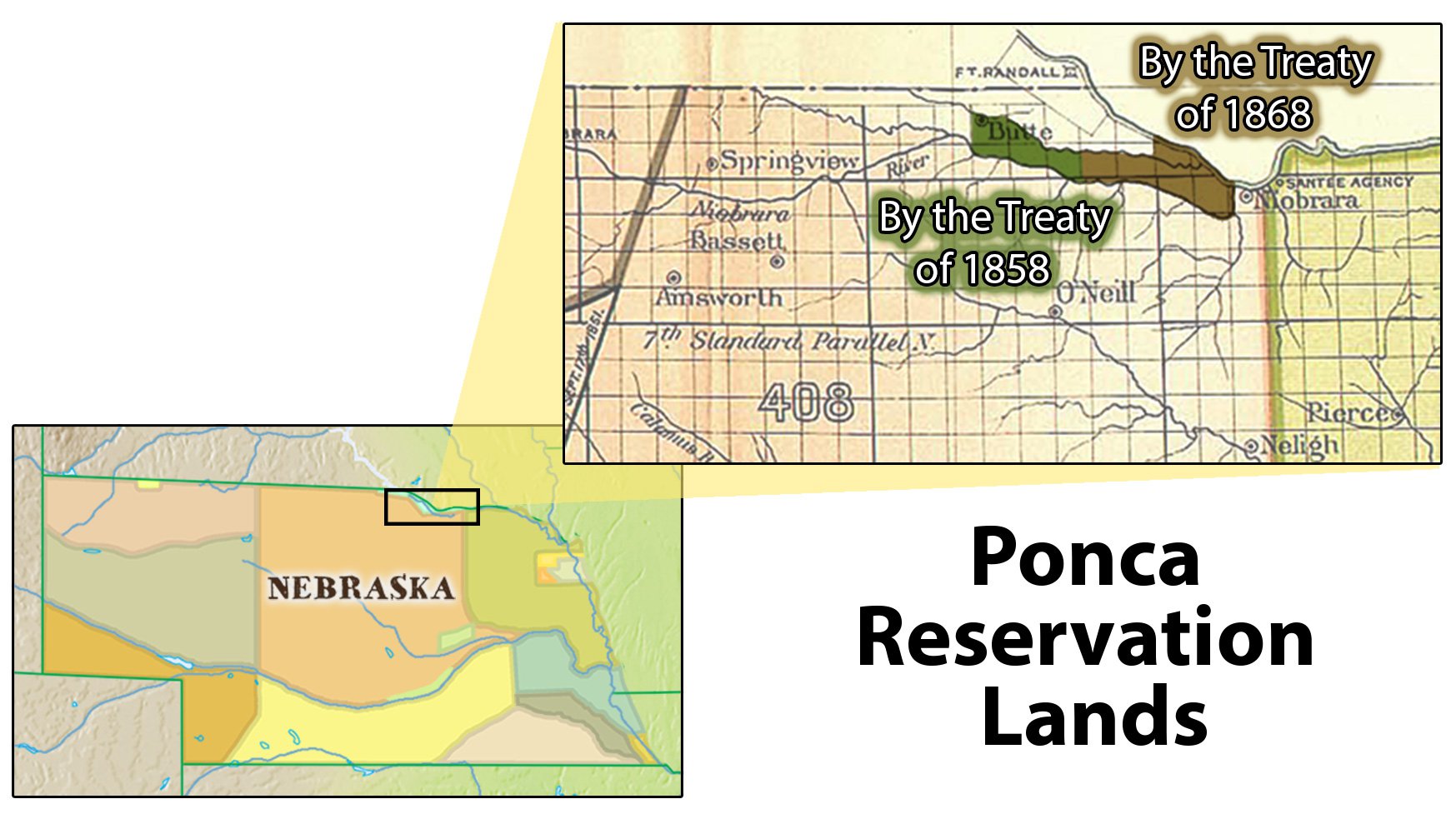

*I looked up the original references for each of these finds, and noticed an interesting detail in the writeup of Ponca Creek. In Meteoric Iron from the Dakota Territory, by Charles T. Jackson, in the American Journal of Science Ser. 2 Vol. 36, July-Nov. 1863, Jackson wrote that the iron had been received from “John B. Hoffman, Esq., US Indian Agent for the Ponca Tribe.” At the time, the Ponca Tribe consisted of just several hundred individuals and they occupied a limited range of NE Nebraska:

…Did you happen to notice Ainsworth on that map? Ainsworth was less than 50 miles Southwest of the Ponca Tribe’s territory circa 1860, when Ponca Creek was recovered. That seems to be the general region where the pieces of this meteorite fell. Laddonia, Missouri is located about 480 miles to the Southeast.

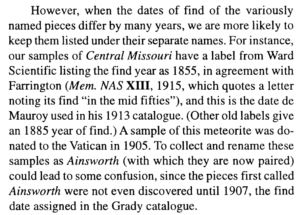

But, “Central Missouri” was published as the find location of that iron in its earliest recorded descriptions. So, while the labels with this ‘mystery slice’ don’t appear to be accurate, the error is historically well-documented. Buchwald offered his thoughts:

“”Central Missouri” is a fragment transported eastward by man. Perhaps one might even conclude that “Central Missouri” is part or the remainder of the hitherto evasive Ponca Creek mass, which was known to exist about 1860 but never reached Dr. C.T. Jackson…”

Given the timeline, approximate sizes of the masses, etc., that does seem like a very real possibility. There might have been only two recovered masses, and the “lost” portion of Ponca Creek may have turned into “Central Missouri.” We’ll probably never know for sure. To get to the bottom of it, someone would probably need to track down all of the distributed pieces labelled as each find and then try to physically reassemble the masses.

New information comes to light!

After I’d figured out what this slice was, Peter took a deeper dive into the history of Central Missouri, Ainsworth, and Ponca Creek. He dug up some old newspaper articles that ~rewrite the early history of the Ainsworth mass.

This page is already a little long, so please see here for the true story of Ainsworth’s discovery: a tale of mystery, intrigue, and death. Really surprised me.

Lessons learned?

In the end, I’d chanced upon the identity of this slice not in a catalogue, but in an account of the problems institutional curators had run into while cataloguing specimens of this very meteorite.

“Central Missouri” even had its own thorough write-up in Buchwald, right after Ainsworth. And Ponca Creek, did, too. You can read them all here. As for why I didn’t catch those entries…if you scroll down to the entry for “Albuquerque” in that same PDF, it’s a good example of how Buchwald usually addressed paired or transported irons in the Handbook, and it’s why I didn’t notice the related entries after Ainsworth. “Albuquerque” was a transported mass of Canyon Diablo, and its description is alphabetically where it should be, with the other “A”s. It’s not described after Canyon Diablo, alphabetically out of place. Central Missouri and Ponca Creek, however, are. Go figure.

The identity of this specimen was mostly tricky to pin down because “Central Missouri” isn’t in the online Meteoritical Bulletin Database. “Central Missouri” is listed as a pseudonym for Ainsworth, and pseudonyms are treated differently by the online Database. They won’t show up in any type or location searches, and will only turn up after you type in part of them (in this case, “Central” or “Missouri”) into the name field and hit search. If you did that, you’d see this. See those “Synonyms” near the bottom?

The trouble is that the Bulletin Database auto-completes meteorite names entered into the search field, but it apparently only does that for approved names – not pseudonyms. So after typing “Central” or “Missouri” into the name field and seeing it respond with “no matches found,” you’d be led to believe that neither word was part of any meteorite’s name. And why would you bother clicking “search” when you can already see there are no matching search results? …I learned a lot about the quirks of the Database’s search function this past week.

This was a really fun riddle. 10/10.

Anyway, here are some more photos of the specimen. The meteorite slice is set in typeset metal – an alloy of lead, antimony, and tin used to make typeset letters for old printing presses. The typeset metal was chiseled on the front face to give it that interesting texture. Typeset metal is around 10g/cc — around 50% more dense than iron — making it difficult to estimate the weight of the embedded meteorite slice. Altogether, the display weighs a little over 2.7 kilograms, but I would guess the meteorite slice itself weighs somewhere between…300 and 800 grams? It’s hard to tell. Don’t really care: it’s cool and I’m just glad I was able to figure out what it is.

Epilogue

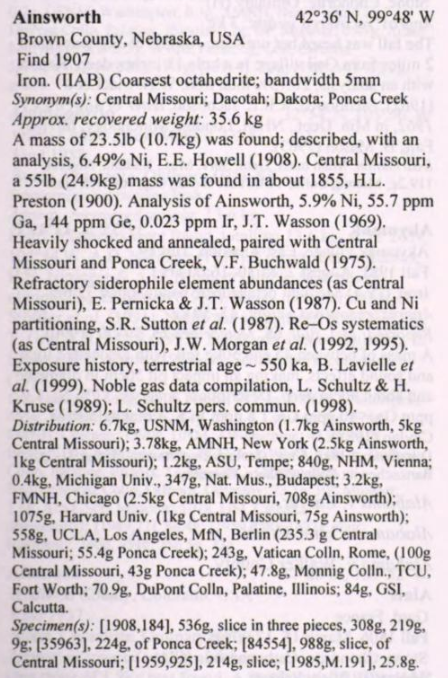

I pulled out a copy of Grady’s Catalogue of Meteorites (2000) while making this page, to have a look at the modern distribution of this iron in collections.

As it turns out, cracking the book would have saved me a lot of time and effort:

If I’d checked the physical Catalogue as a reference, instead of using the online Meteoritical Bulletin Database, I would have figured out the identity of this slice in my initial search through the IIABs. It would have taken probably a half hour, instead of…two days…

![]()

If you don’t have a copy of Grady’s Catalogue yet, this shows why it’s a nice resource to have around. It contains much more information about historic meteorites than you’ll find in the online Meteoritical Bulletin Database.

And I would add one additional comment.

Experts who have studied iron meteorites, like Vagn buchwald, John Wasson, etc., used the trace element concentrations of these 2-3 irons to determine that they were paired, even in the absence of good documentation or records showing where these specimens came from. Iron meteorites are rare, and, out of the ~1,400 currently published irons, almost no two are chemically indistinguishable (via NAA). So, when two identical irons turned up, even at different times and in different places, it often made sense to assume that one of them was transported by humans. And that’s even more true, today.

In modern times, common iron meteorites like Campo del Cielo, Canyon Diablo, Odessa, Sikhote Alin, Toluca, Nantan, and others have become cheap commodities, readily available anywhere in the world.

And a few dozen “new” irons chemically and otherwise identical to Sikhote Alin, Canyon Diablo, Campo del Cielo, etc., have been found around the world over the past few decades, including several in the American Southwest. “Finders” have even managed to get some of these dubious finds published in the Meteoritical Bulletin, as “new” irons.

Newer analytical methods like ICP-MS don’t currently offer the precision necessary to tell iron meteorites apart based on their trace elements. In my personal experience: around half of the “new” irons sent in to UCLA for analysis turned out to be transported pieces of common meteorites, analytically identifiable as common irons. Even when they came from sources we had no obvious reason to question. Labs today simply don’t have the ability to be so critical. It’s a real problem.

Always be mindful. There’s a lot of money to be made if someone “finds” a Campo and manages to get it published as a new iron, and that kind of thing has been happening more and more over the past several years.